As England moves into another lockdown tomorrow, yesterday I took the opportunity to go out while I could to visit the British Museum’s latest exhibition.

Arctic: Culture and Climate examines the creative resilience of the indigenous peoples of the region, using local resources to survive and adapt to their environment over the past 30,000 years. There are more than 40 different ethnic groups, but they share many cultural traits and were trading and communicating with each other long before the “southerners” arrived.

“We’re from the High Arctic”, says Inuit seamstress Regilee Ootoova. “We rely on what’s available to us.” And what’s available to them is largely animals – seals and walrus, reindeer and caribou, fish and whales. They view hunting as the giving and receiving of gifts – that animals will only give themselves up to those who treat them with respect, and that the souls of these animals will be reborn, keeping them infinitely renewable.

But animals are not just hunted for food – almost every scrap of them seems to be used in some way. Here I focus mainly on textile and basketry items, but there are some fine carvings and paintings in the exhibition too.

This bag is made of salmon skin, seal oesophagus and caribou fur. There’s a very good post on the British Museum blog on how fish skin is processed.

Seal gut, being waterproof and breathable, was used to make parkas. The seams of this one incorporate beach grass – if any moisture enters the seam, the grass absorbs it and swells, thus tightening the seam and keeping the wearer dry.

Another bag, this time made of duck feet.

This lovely basket is made of baleen, with a walrus ivory handle.

Baleen, sourced from whales, is flexible and does not freeze, so it was also used for making sieves to scoop away slush from ice fishing holes. The frame of this one is made of reindeer antler.

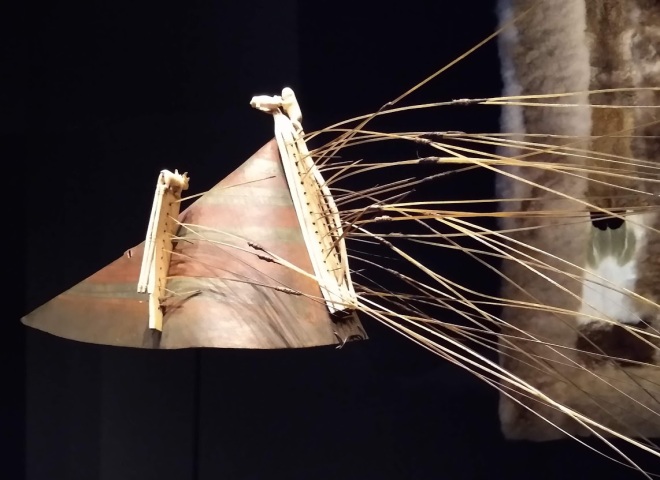

Certain animal characteristics were often thought to endow the wearer with similar powers. So this visor decorated with sealion whiskers bestowed the animal’s hunting prowess on its wearer – each whisker represented a successful hunt.

Sometimes hunters would mimic animals so they could get closer to them. This ice scratcher, made from seal claws bound to driftwood with sinew, made a noise like a seal sunning itself on ice, lulling the prey back to sleep so a hunter could approach it unawares.

Plant materials

As well as animal products, beach grass was woven into mats, bags and socks.

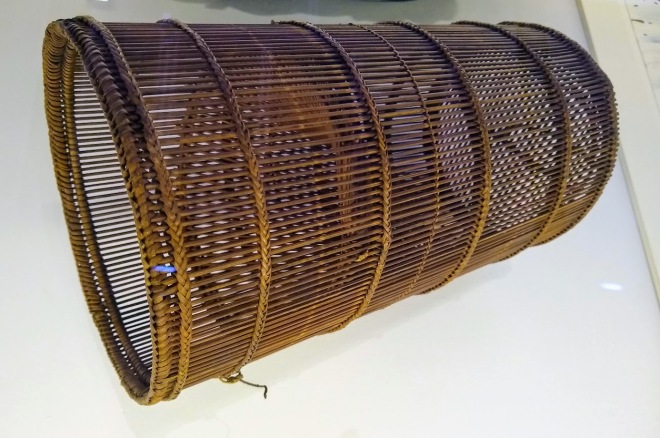

Wooden fish traps like this were placed into holes cut into frozen rivers.

In north-east Russia the Sakha people hold a summer festival, or yhyakh, asking the gods for good weather and plentiful pastures. As part of the celebrations, large birch bark containers stitched together with horsehair are filled with meat, wheat porridge and berries with whipped cream for serving to everyone.

Integrating traded materials

As Arctic peoples came into contact with “southerners”, they started incorporating their materials into their tools and garments. The first Europeans arriving in the Bering Strait traded beads for furs. This national costume of the Kalaallit, Greenland’s largest Inuit group, incorporates sealskin sewing with the embroidery and beadwork on northern Europe.

In the 19th century, Moravian missionaries encouraged Yupiit basketmakers to make coiled baskets that appealed to collectors and tourists, like this one with a puffin design.

More recently, on Nunavak Island, Alaska, basketmakers have recycled nylon fishing rope washed up on the beach to crochet into colourful bags.

Sadly, as in so many other instances, this contact led to colonisation, forced conversion, imposed migration and forced settlement. And now there’s climate change.

The exhibition ends on a hopeful note, with displays curated by two indigenous organisations explaining how they are transforming their heritage by adapting, innovating, collaborating and resisting to determine their own future.

Arctic: Culture and Climate is due to run at the British Museum until 21 February 2021, although it’s temporarily closed until at least 2 December due to lockdown. Please check the website for updates.

Kim you’ve had me totally captivated. Thank you.

The resourcefulness of the indigenous people, their respect for their surroundings & their ability to use everything, nothing wasted, (typical of so many First Nation peoples) should be a subject taught to everyone.

You’re right Antje – we could learn a lot from their resourcefulness and respect for the environment. 🙂

😁

Thank you for sharing this Kim. I know it may disgust some people, but when you live in harsh conditions, you need to utilise what is available. I like that nothing is wasted and that people may have found a use for something that others would throw away. Circumstances also determine how creative a culture can be, especially when survival is at the top of the list.

Thanks Arlene. I know that some people are distressed at the thought of hunting and killing animals, but given their circumstances the Arctic peoples had little choice if they weren’t to starve. And they did it sustainably, only taking what they needed and making use of every possible scrap. Something that we could all learn from. 🙂

Thank you Kim for giving me a glimpse of what must be an extraordinary exhibition.

Thank you – glad you found it interesting! ☺️