Alexander Calder is probably best known for his mobiles, so there’s no obvious connection with textiles. But a couple of years ago, when I made a mobile of felt windmills for an exhibition at Brixton Windmill, I studied quite a few of his mobiles. So I was inevitably drawn to Alexander Calder: Performing Sculpture at Tate Modern.

Calder was an innovator from the off. Although his mother was a painter and his father was a sculptor, he initially trained as an engineer before attending evening classes in drawing. The exhibition opens with displays of his wonderful wire sculptures, which use a linear substance to describe volume. In his circus figures a gentle arc evokes a pectoral muscle, while squiggles, spirals and coils become genitals, pubic hair and breasts.

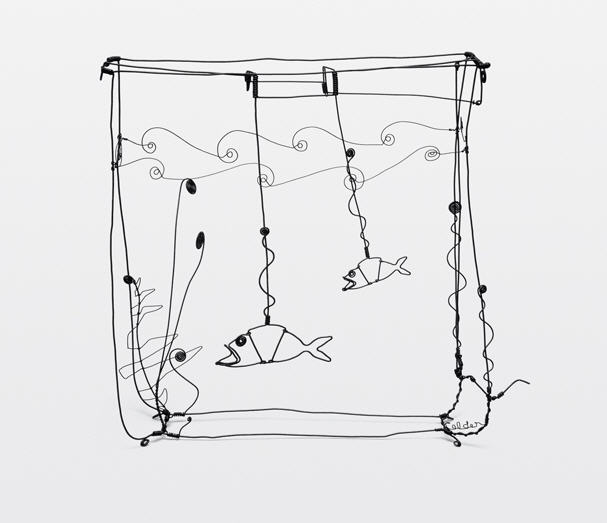

Copyright The Calder Foundation, New York/ DACS, London

The rangy tension of a leopard becomes a series of tight coils, while an elephant sits more solidly on four hollow wire legs.

Even at this stage, Calder was fascinated by the idea of movement in sculpture – Goldfish Bowl, the first piece in the exhibition, included a small wire crank that, when turned, caused the fish to wriggle from side to side.

Unfortunately, for conservation reasons, none of the motorised sculptures in the exhibition move, so it’s worth investing in the audio guide, which contains footage of some of the pieces in action.

Calder also captured portraits in wire of several artists friends, including Léger and Miró. But it was a visit to the studio of abstract artist Piet Mondrian in 1930 that he described as “the shock that converted me…like the baby being slapped to make its lungs start working”.

After Mondrian disagreed with his suggestion to make the geometric elements move about, Calder started experimenting with his own abstract sculpture, suspending spheres and other shapes on wires to allow free movement.

Other artists of this period, including the Cubists and Futurists, were attempting to convey the feeling of movement in their work. Calder drew on his engineering background to make it a reality, installing small motors to “control the thing like the choreography in a ballet”, as in Black Frame, below.

He even went on to make real stage sets for Martha Graham and Erik Satie, but felt frustrated about the lack of total control and that his efforts were relegated to the status of props.

In 1938 he took part in the New York World’s Fair, creating three maquettes for “ballet objects”, consisting of revolving elements creating a choreographed movement.

In the 1950s, Calder made a connection between his work and how the universe worked: “The idea of detached bodies floating in space, of different sizes and densities…some at rest, while others move in peculiar manners, seems to me the ideal source of form.” Ironically, much of his work in this room consists of elements held in fixed positions by steel wires.

One of the exceptions is A Universe, in which red and white balls originally moved along wires – apparently Albert Einstein stood watching it for 40 minutes when it was first exhibited at the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

By contrast, room 9 brings together a stunning collection of Calder’s mobiles. After he moved to an old farm in Roxbury, Connecticut, the forms became more organic and less geometric in form. Calder saw the shadows cast by the mobiles as part of the work, and the way they have been hung and lit in this room is particularly striking.

The following room features mobiles incorporating small gongs, which rely on the random movement to produce sounds. As visitors are not permitted to touch or blow on the mobiles, you have to hope that the air conditioning will move them in the right way to make music. 🙂

The exhibition finishes with spectacular 3.5m Black Widow sculpture, loaned abroad for the first time by the Institute of Architects of Brazil in São Paulo.

Alexander Calder: Performing Sculpture runs at Tate Modern until 3 April 2016.