This exhibition, in the sumptuous surroundings of Two Temple Place, features highlights from the eclectic collections of seven female textile collectors from the 19th century to the present day. It’s a splendid mix of beautiful embroidery and costume, elegant homeware, and art textiles.

Edith Durham (1863-1944)

Edith Durham was an artist who travelled extensively throughout the Balkans, especially Albania, in the period before the First World War. Journeying on horseback with a local guide, she collected many examples of traditional dress, textiles, and jewellery, making detailed notes and sketches on their cultural significance and local customs. After she died her collections were donated to the Bankfield Museum in Halifax.

Louisa Pesel (1870-1947)

If you’ve read A Single Thread by Tracy Chevalier, you’ll instantly recognise the name. Louisa Pesel was a distinguished embroidery artist and historian, teacher and writer. After studying at the Royal College of Art she went on to become director of the Royal Hellenic School of Needlework and Lace in Athens. When she moved back to Britain, firstly to Bradford and then to Hampshire, she started teaching people to stitch, whether for employment, therapy or pleasure. Her students included shell-shocked soldiers, refugees, and volunteers at Winchester Cathedral – the subject of Chevalier’s novel.

Olive Matthews (1887-1979)

London resident Olive Matthews started collecting as a child, saving her pocket money to buy costumes from Caledonian Road market. Such items were not regarded as particularly collectable at the time, so she prided herself on getting a bargain, not paying more than £5 for anything. At the beginning of the Second World War she moved with her family to Virginia Water in Surrey, and her collection formed a key part of the Chertsey Museum when it was set up in 1965.

Enid Marx (1902-1998)

Enid Marx was a leading designer probably best known for her industrial textile designs, such as the seat fabric for London Transport. Before that, she was an apprentice with block printers Phyllis Barron and Dorothy Larcher, which led her to explore the process of printing fabric with wood blocks and natural dyes. She was also a great collector, along with historian Margaret Lambert, of folk art and popular ephemera, some of which are included in the exhibition. The Marx-Lambert collection is now at Compton Verney.

Muriel Rose (1897-1986)

Muriel Rose was a leading advocate for 20th-century British craft, determined to put craft on the same footing as painting and sculpture. She set up the Little Gallery near Sloane Square in London in 1928, where she exhibited the work of textile artists such as Enid Marx, Barron and Larcher, and weaver Ethel Mairet, as well as potters such as Bernard Leach. She travelled and collected extensively, both abroad and closer to home – for example, she sold high-quality handmade quilts by Durham miners’ wives alongside work from Japan and Mexico. She went on to become Director of Craft and Industrial Design at the British Council and a founder trustee of the Crafts Study Centre (now in Farnham).

Dr Jennifer Harris

Jennifer Harris was responsible for building up Britain’s foremost collection of contemporary textile art at the Whitworth Art Gallery in Manchester. From 1982 to 2016 she was the deputy director and curator of textiles, collecting “statement acquisitions” and more speculative pieces made with traditional craft techniques but more conceptual and sculptural in form. Examples of pieces she collected included some stunning indigo work from an exhibition she curated in 2007 and large-scale machine-embroidered “drawings” by Alice Kettle.

Nima Poovaya-Smith

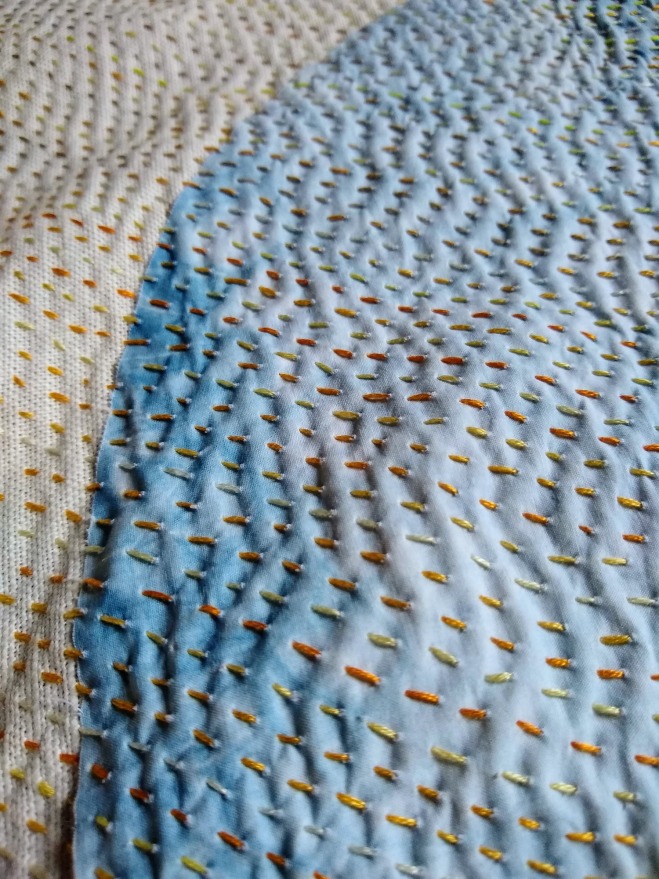

As senior keeper of the International Collections at Cartwright Hall Art Gallery in Bradford from 1985 to 1998, Nima Poovaya-Smith made the collections more representative of Bradford’s diversity. Reflecting the big Pakistani community, the exhibition includes a lovely stitched kantha piece as well as phulkari embroidery.

Unbound: Visionary Women Collecting Textiles runs at Two Temple Place until 19 April 2020.