Regular followers of this blog will know that my primary textile interests are to do with form and texture. So I haven’t paid much attention to weaving (although my recent explorations in basketry rely on weaving techniques). Two recent events have punctured this insularity.

The Tate Modern exhibition on Anni Albers opened about 10 days ago. After its exhibition on Sonia Delaunay in 2015 this seems to be continuing the art world’s discovery that textiles can be art too.

Ironically, Albers faced a similar prejudice when she attended the Bauhaus art school in Weimar, Germany, in 1922. Despite its pretensions to equality, women students were often shepherded into the weaving classes rather than painting or sculpture.

But Albers made the most of the hand she was dealt. Weaving, with its warp and weft, admirably fitted in with the modernist grid concept, but by using unusual materials, such as cellophane and metallic threads, her pieces created painterly effects such as the impression of shifting light as well as retaining their texture.

In 1933 the Nazis forced the Bauhaus school to close, and Albers moved to the US with her husband Josef. As well as teaching, she started making “pictorial weavings” – artworks to be hung on a wall rather than used as fabric. I found these to be some of her most interesting pieces, experimenting with twisted warp threads, double warp layers, and gathering yarn to create bobbles.

As well as art textiles, Albers also worked on architectural commissions, including room dividers and window covers for furniture designer Florence Knoll in 1951. These included very open weave lattices in linen that filtered light while also allowing air to circulate.

Albers’ most ambitious pictorial weaving was a memorial to the 6 million Jews killed in the Holocaust, commissioned by the Jewish Museum in New York. Although she was from a Jewish family, Albers had been baptised as a Protestant and didn’t regard herself as really Jewish. But her piece, Six Prayers, beautifully interprets the Torah scrolls and Hebrew script.

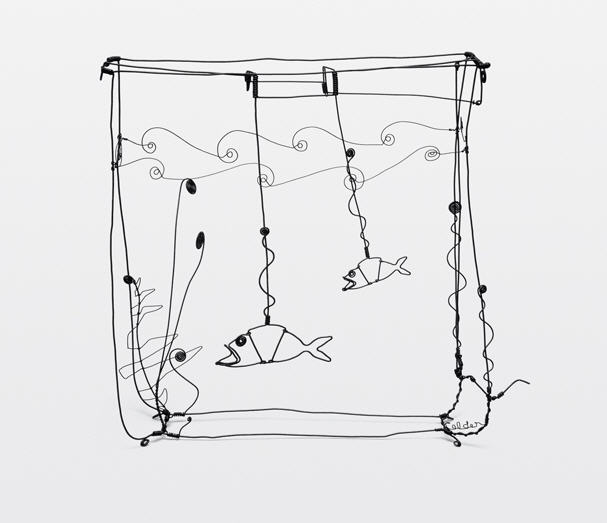

Albers was a master of technique, creating multilayered, highly textured pieces. But she also saw thread as a material she could use to “draw”.

She also turned to more conventional drawing, painting, embossing and printing techniques in a series of entangled knots, one of which was interpreted in this rug.

Albers didn’t keep many sketchbooks, but she did produce lots of samples, which are absolutely fascinating.

Albers is probably best known for her seminal 1965 book On Weaving. The exhibition includes some of the source material she gathered for the book, including woven pieces from around the world.

Anni Albers continues at Tate Modern until 27 January 2019.

On a slightly smaller scale, the other event that made me reassess weaving was the Praktis 2018 exhibition in the lovely Bury Court Farm in Hampshire. Two friends, Barbara Kennington and Lucy Goffin (aka Material Being) were exhibiting some of their exquisite embroidered waistcoats, stitched pictures and paintings.

Also taking part was weaver Ann Richards, who uses high twist yarns to create pleating that happens spontaneously when the fabric is soaked in water. Ann did a demonstration while I was there, putting a small woven piece in a glass of water, whereupon it pleated by itself, apparently by magic!

The pleats instantly reminded me of arashi shibori, and I couldn’t resist buying a bracelet.

Along with two other textile artists, Alison Ellen and Deirdre Wood, Ann is taking part in the exhibition Soft Engineering: Textiles Taking Shape, which will be moving to Whitchurch Silk Mill in Hampshire next year.